Gene Revolution: Transforming Pakistan's Agriculture

Explore how the gene revolution can address chronic yield gaps in Pakistan's agriculture, conserve water, and adapt to climate change, unlocking new economic opportunities in crops and livestock.

POLICY BRIEFS

Wajhullah Fahim

8/12/2025

Half a century ago, Pakistan joined the world in celebrating the Green Revolution, a period when improved seeds, fertilizers, and irrigation transformed agriculture, helping feed millions. Today, however, the benefits of that revolution are plateauing. Yields of major crops are stagnating, water resources are under strain, and climate change is taking an ever-tougher toll.

Enter the Gene Revolution. This new era is powered by biotechnology, the deliberate alteration, recombination, and transfer of DNA to create plants and animals with new, desirable traits. In agriculture, it means crops that can resist pests without chemical sprays, withstand extreme heat or drought, and deliver higher yields from the same or even less land. It also promises livestock that are healthier, more productive, and better suited to local environments.

For Pakistan, the potential is immense. Genetically engineered crops could help achieve Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger) by boosting yields, reducing losses, and cutting reliance on costly agrochemicals. With climate-resilient varieties, farmers could adapt to the floods, droughts, and temperature swings that are already reshaping the growing season. For consumers, the benefits could mean a more stable food supply at affordable prices.

Yet, despite the promise, Pakistan’s agricultural system is struggling to capture the benefits of this revolution. The sector contributes around 24% of GDP and employs 37% of the labor force, but its productivity lags behind global competitors. Four intertwined challenges make the case for urgent transformation.

The Challenges Holding Back Pakistan’s Agriculture

Pakistan ranks among the top ten global producers of wheat, rice, and sugarcane — yet its yields per hectare are among the lowest in the world. Farmers work hard but harvest less than their counterparts in countries like China, Egypt, or even neighboring India. This productivity gap translates into lost income for farmers and higher food prices for consumers.

Four crops, wheat, rice, sugarcane, and cotton, consume about 80% of Pakistan’s available water, yet together contribute just 5% to GDP (Maqbool, 2022). In a country already facing severe water scarcity, continuing to grow these crops using traditional, water-intensive methods is economically and environmentally unsustainable.

Pakistan ranks among the top ten most climate-vulnerable countries (Eckstein et al., 2019). The 2022 floods alone caused an estimated US$3.7 billion in agricultural losses (GoP, 2023). Rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, and shifting seasons threaten both crop and livestock production, making resilience a top priority.

The livestock sector accounts for 61% of agricultural value added and about 15% of GDP (GoP, 2024). Yet productivity is low due to poor genetics, limited disease control, and inadequate investment. Farmers often face devastating losses from preventable diseases, and milk and meat yields remain far below international benchmarks (Ghafar et al., 2020).

Given these challenges, Pakistan’s earlier “Green Revolution” tools, better irrigation, fertilizers, and conventional breeding, are no longer enough. What is needed is a Gene Revolution tailored to the country’s unique needs.

The Barriers to a Gene Revolution in Pakistan

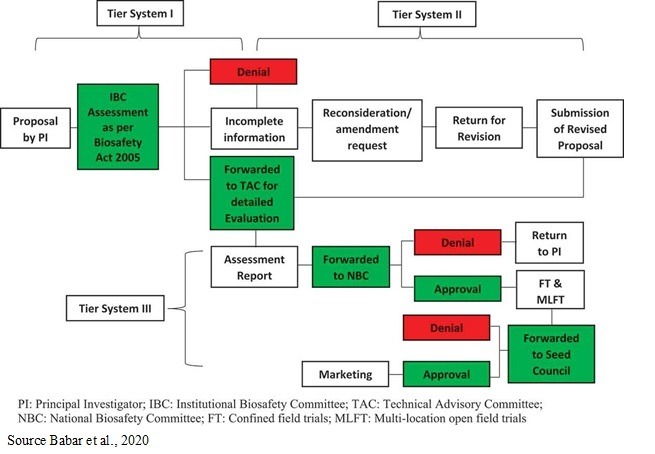

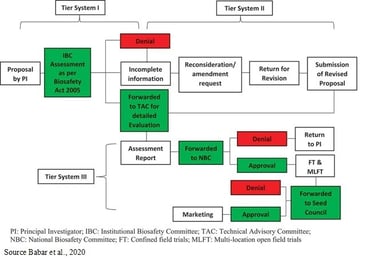

Globally, regulation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) began in the late 20th century, with countries like the United States introducing biosafety rules in 1984 and China in 1997. Pakistan established its National Biosafety Committee (NBC) in 1994 and passed the Pakistan Biosafety Act in 2005. The Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency (Pak-EPA) then set up the National Biosafety Centre to oversee implementation.

However, the 18th Constitutional Amendment shifted environmental matters to the provinces, creating regulatory confusion and turf battles between federal and provincial authorities. The result: overlapping jurisdictions, lengthy approval processes, and a legal stalemate. In 2014, for example, the Lahore High Court directed the federal government to issue licenses for GM cotton and maize, but the Supreme Court suspended the order a month later (Ebrahim, 2014).

Today, GMO approval in Pakistan involves multiple layers of committees and agencies, a process so cumbersome it discourages innovation.

Figure 1: GMO Approval Process in Pakistan

Some religious leaders and communities view genetic modification as tampering with nature or divine creation. Without proper engagement, these concerns can turn into organized resistance, stalling adoption of beneficial technologies.

For private-sector innovators, patents and plant breeders’ rights are essential incentives. While Pakistan passed the Seed (Amendment) Act 2015 and the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act 2016, the requirement to submit seed samples to the National Agricultural Research Centre (NARC) for verification adds another bureaucratic hurdle, slowing commercialization.

The agriculture sector intersects with multiple ministries and departments from water and irrigation to livestock and climate change. After the 18th Amendment, some of these responsibilities shifted to provinces while others remained federal, weakening collaboration. Public-sector universities, research boards like PARB, and think tanks like PARC and PSF work on gene engineering projects, but without a robust information-sharing framework, efforts remain fragmented.

The Way Forward: Catalyzing Pakistan’s Gene Revolution

Pakistan’s biosafety framework needs an overhaul to eliminate unnecessary overlap between federal and provincial authorities. One option is to adopt internationally recognized third-party certification systems such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) or the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC).

E-governance can make applications faster and more transparent, reducing the discretionary power of bureaucrats. Federal agencies could focus on import/export regulation, while provinces develop and enforce locally relevant biosafety rules using modern tools like satellite imagery and drones.

Turkiye offers a successful example: by holding open dialogues, creating ethical review boards, and involving religious scholars in policy discussions, the government built public confidence in biotechnology. Pakistan can replicate this model, ensuring that genetic advancements align with cultural and religious principles while dispelling myths about genetic modification.

A National Gene Revolution Steering Committee could bring together agricultural scientists, environmentalists, livestock experts, economists, and representatives from federal and provincial governments. Meeting quarterly, this body would share data, track progress, and coordinate projects across the public and private sectors.

Biotechnology adoption depends on more than government approval; farmers need to understand its benefits and practical application. Demonstration plots, farmer field schools, and mobile-based advisory services could bridge the knowledge gap, ensuring that smallholders as well as large-scale producers’ benefit.

Conclusion

The Green Revolution transformed Pakistan’s agriculture once before, but the challenges of the 21st century demand new tools. The Gene Revolution, if pursued strategically, can help Pakistan overcome chronic yield gaps, conserve precious water, adapt to climate change, and unlock new economic opportunities in both crops and livestock.

Yet technology alone is not enough. Without streamlined regulations, strong public engagement, effective intellectual property protections, and robust institutional coordination, the promise of biotechnology will remain out of reach. By learning from global best practices and adapting them to local realities, Pakistan can make the leap from potential to practice, securing a food-secure, climate-resilient future for its people.

References: Babar et al.; Ebrahim; Eckstein et al.; Ghafar et al.; GoP; Maqbool; Sherin

Please note that the views expressed in this article are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of any organization.

The writer is an independent researcher and can be reached at wajjiccs@gmail.com

Related Stories

📬 Stay Connected

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive research updates, publication calls, and ambassador spotlights directly in your inbox.

🔒 We respect your privacy.

🧭 About Us

The Agricultural Economist is your weekly guide to the latest trends, research, and insights in food systems, climate resilience, rural transformation, and agri-policy.

🖋 Published by The AgEcon Frontiers (sPvt) Ltd. (TAEF) a knowledge-driven platform dedicated to advancing research, policy, and innovation in agricultural economics, food systems, environmental sustainability, and rural transformation. We connect scholars, practitioners, and policymakers to foster inclusive, evidence-based solutions for a resilient future.

The Agricultural Economist © 2024

All rights of 'The Agricultural Economist' are reserved with TAEF